Why medical mental health services doubt psychological typing

It doesn't take a genius to know that there are different types of people. We only need to think about our own family. Or about the patients we will be seeing in today's clinic. How each person has their own striking qualities and their own (to us) annoying tendencies. It is evident to anyone with enough experience of people. Some of these qualities have been systematically proven as reflecting real physiological differences between people. Highly sensitive people, and introversion vs extraversion spring to mind. So why is psychiatry practised as if differences of this fundamental kind are irrelevant to their mental health and recovery? Why are we apparently reluctant to systematise these qualities and investigate their relationship to mental health issues and their treatment?

None of us can see ourselves

Jung (a psychiatrist himself) had an interesting take on this. In his 'Psychological Types', in the very first page of the introduction in fact, he notes that 'In respect of one's own personality one's judgement is as a rule extraordinarily clouded.'

Again, we see this in other people. We mutually roll our eyes at the person who only talks to another person when they need something from them, for example, or at the person who never leaves a room once because they never check they have what they need first. You only have to sit down and predict one or two things members of your family will do or say at a family gathering to know this is true. Martha Beck designed a hilarious game around this idea

Often people can't see the thing about themselves that is most obvious to everyone else. The messy mother who's always losing things claims to be 'terribly well organised', the self-centred person sees themselves as having 'the patience of a saint' and the 'free spirit' will make all sorts of pernickerty rules about other peoples' behaviour, or what they are allowed to say in their presence.

In other words, there's something about experiencing our lives from the inside that means we cannot see ourselves clearly.

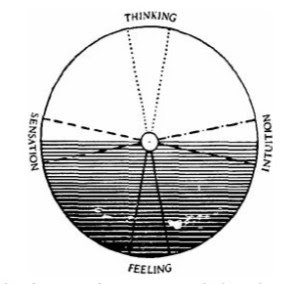

Jung's typological model showing how people of his own psychological type have conscious access to and responsibility for their thinking, some access to sensation and intuition, but very little access to or responsibility for feeling judgements.

Jung's model is that our appearance and behaviour in the world is a result of the parts of us that we are unaware of, just as much as (or perhaps even more than) the parts that we are conscious of and tend to take responsiblity for. More detail of the specific meanings of these words in this model will be coming in later posts. For the time being the important thing is the way we are not aware of not being aware.

So according to our own repeated experience with people we know and to Jung's model, we are driven by things that we are not aware of, despise even, and these things are often more powerful engines of our lives than we know.

Personality quirks, moi?

I have talked about this so far in terms of how we see other people around us, but whenever we talk about this subject we have to be aware of how much we do not and cannot know about ourselves and our own unconscious motivations. How much you, dear reader, do not and cannot know yourself and the filters through which you see the world. Because however much work we have done on making our own unconscious conscious, we are built no different than anyone else in this way.

So looking at this one square in the face, the one thing we can be sure of about psychological typing is that answering a quesionnaire about it on our own behalf is going to be a very imprecise, confused or even at times the exact opposite of our actual type. It will reveal only our inevitably erroneous self-image and nothing about the parts of us that are clear as day to anyone and everyone who knows us.

How we measure personality now

So the first principle about measuring someone's personality is that relying on self-report questionnaires is inevitably flawed. And you will no doubt be aware that almost all personality traits are measured in this way.

At the beginning of personality questionnaires there is often an instruction to the testee to be wary of answering the way they think they should answer or how they would prefer to be. But it is a basic tenet of Jung's theory that essentially we don't have this choice. Since we are unconscious of our biases we are unable to correct for them.

This is the way information about us is collected with the following very popular and common personality tests:

Big Five

MBTI

DISC

Enneagram

Clifton Strengths Finder

So any results and correlations from these tests will be correlating data with self-understanding rather than with an actual difference in the make-up of the person. You can understand this as what it appears to be - our opinions about our own behaviour is collected, and then fed back to us in the form of graphs and piecharts and sometimes percentages. So it is unsurprising that the conclusions are 'frighteningly accurate' and reassuring to us.

But obviously what is being measured here is not actual behavioural information but our self-opinion, which is much like the self-image of a person after a parietal stroke - we are not even aware of being unable to see part of ourselves. Another example of this self-blindness would be the well-known tendency of people to ignore or discount calories from some things, while being very careful about counting them from other things. Not through a conscious wish to cheat, but through an unconscious wish to have their cake and eat it too.

And surprise, surprise, clear correlations of these tests and mental health symptoms or outcomes are hard to come by, So we evidence-based doctors dismiss the whole subject area and continue without the benefits it could potentially bring to our patients.

Why it has developed in this way - scaling

Initially personality typing was done by Jung and his followers on their psychotherapy patients - a psychiatrist or psychologist in prolonged personal conversation with a person. The professional got to know them as another person, and was to a degree aware of their own inner bias in typing, and was therefore able to formulate a relatively 'objective' type for them.

Once personality typing began to be used for career direction and human resources it needed to be scaled, and large numbers of people had to be 'typed' quickly by people with relatively little time or training. The pragmatic solution was a self-report questionnaire, sometimes with a follow-up interview with a more thoroughly trained professional, but always with the final decision being that of the testee. I believe the first of these was the Myers Briggs Personality Instrument Form A, which was copyrighted in 1943.

If I cannot see myself clearly, then the final arbitor of my type has to be not whether it sits right with me, but whether it sits right with people who know me.

Popularity

So the needs of scaling were a large reason for this change from professional conclusions to personal identification, but I would hazard an experienced guess that the other reason is likely to be the response of the testees. Nobody likes to think other people know them better than they know themselves. For some types that would actually be an aspect of their greatest fear! And fundamentally we all think of ourselves as embodying the qualities that we identify with - the parts of ourselves that are conscious of, approve of or see as desireable.

Having someone tell us that our official type is in fact something we are unconscious of, disapprove of or despise in others is not going to endear us to that typing method!

And anyway what has psychological typing got to do with diagnosing and treating mental disorders?

Jung's idea that fundamentally our emotional development is accelerated by our accepting those parts of ourselves (and others) that we are unconscious of, and that our identification with only some parts of ourselves is the ultimate cause of all our distress and dissatisfaction, is not generally known or understood in western cultures.

Since senior members of many cultures and spiritual traditions as well as some forms of psychotherapy are based on this idea, that being blind to our own ignorance and powerlessness is the cause of all our distress and dissatisfaction, it would be remiss of us if we didn't explore it further. Especially if we want to be helpful to people mired in distress or dissatifaction.

What if there is some truth in this? What if by understanding this model better we could learn more about ourselves from more objective personality tests? We could learn sympathy for the blind spots of others through accepting ours. And we could learn better how to help our patients out of their distress and dissatisfaction.

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment

Tell me what you think about this idea, your experiences, or just what comes to mind when you read this.